Marta quits her job over an argument with colleagues at work about who should be given credit for a recent deal. Her impulsive emotions bring her to quit without consideration of its far reaching consequences. Is it even important who gets credit for the deal? Could it be settled more rationally? And has she considered where she might find alternative employment?

Gandolfo maintains a toxic relationship with his partner despite knowing it is high time to break up. The comfort of familiarity prevents him from braving the unknown. Every morning he imagines catastrophic scenarios that might extricate him from this situation—accidents, illnesses, obligations that force her relocation—yet fate does not do for him what he must do for himself. He remains paralyzed, unable to pursue what he knows is right.

Roberta’s fixation with order and being in control isolates her from society. She plans each day—and every activity of each day—so meticulously that her friends despair over her lack of spontaneity. She lives alone, works alone, and spends her evenings alone. This way she can execute her plans to the letter. She celebrates her birthday alone too, looking around and wondering, “How come everyone else has such fun together?”

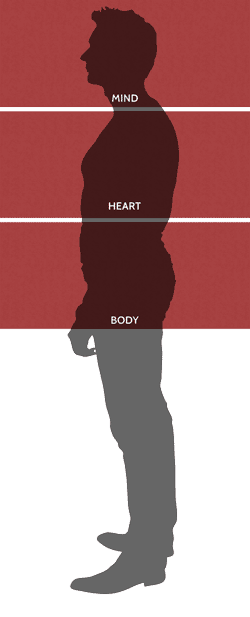

Marta, Gandolfo, and Roberta’s suffering is self-inflicted. One could say that this is the result of an imbalance, with one aspect of their psychology dominating all the rest. As such, they are not particularly unusual. A close study of people in general reveals internal contradictions to be the norm.

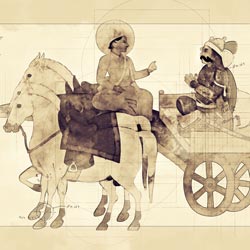

Arjuna with Horse, Carriage, and Driver

Origins of the Carriage Metaphor

One ancient eastern teaching explains these contradictions by using the metaphor of the carriage horse and driver to illustrate the makeup of human beings. This metaphor first appears in the sacred texts that form the foundation of Hinduism—the Vedas—and is elaborated upon in later Hindu texts, such as the Upanishads:

The body as the chariot itself,

The discriminating intellect as the charioteer,

And the mind as reins.

The senses, say the wise, are the horses;

Selfish desires are the roads they travel. i

When the horse, carriage, and driver work in harmony, they form a synergy that transcends their individual capabilities. The driver’s intellect guides the horses’ raw power, while the carriage uses that power to transport more or heavier goods. This cooperation allows for efficient, purposeful movement towards a chosen destination. However, if these elements fall out of sync, the system not only falters, but the activity of each part is impeded. A poorly maintained carriage will slow down even the best of steeds; an untrained horse will drag even the most sophisticated carriage off course; a negligent driver will be unable to direct any horse and carriage. In human terms, this translates as internal conflict, indecision, or self-destructive behavior. The metaphor illustrates how our potential for excellence—or for dysfunction—depends on the delicate balance among our various faculties.

This same metaphor was adopted and adapted by various psychological traditions, most recently by George Gurdjieff:

Arjuna with Horse, Carriage, and Driver

Siddhartha with Horse, Carriage, and Driver

Siddhartha with Horse, Carriage, and Driver

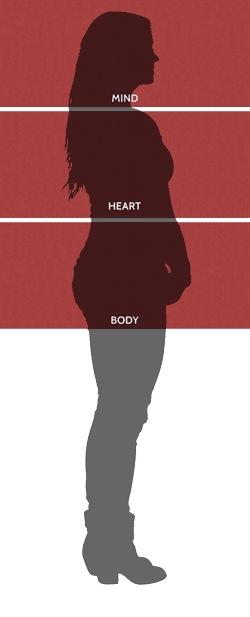

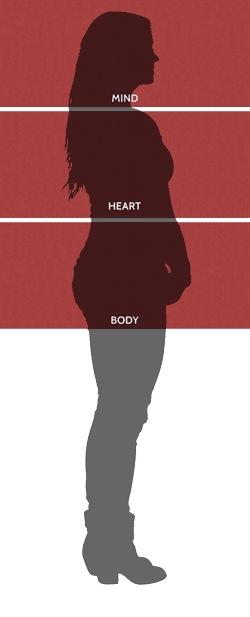

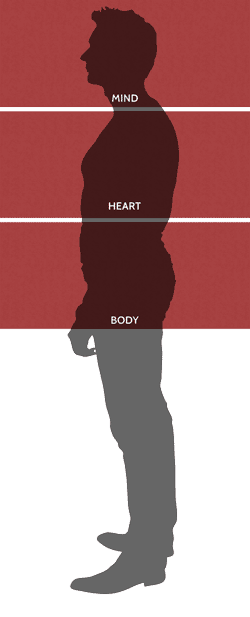

Micro-Cosmos Human as Three-Brained Being

Gurdjieff’s Metaphor of the Carriage Explained

Gurdjieff pointed out that humans are only seemingly unified. Having a single physical body, and answering to a single name, promotes the illusion that we are always one and the same. A closer examination quickly refutes this. Each thought, sensation, and emotion is a separate impulse, originating from separate parts, often unaware of, and even contradicting each other. Gurdjieff’s metaphor of the carriage, horse and driver brings this to life. He correlates each of the three components with the three separate ‘brains’ or ‘functions’ that comprise human psychology:

- The horses symbolize our emotional function,

- The carriage symbolizes our motor function,

- The driver symbolizes our thinking function.

By nature, these three separate functions are by no means attuned to each other. They are undeveloped and untrained.

Continuing with Gurdjieff’s metaphor: The carriage is rusty and its wheels are not balanced. The horses are malnourished and unaccustomed to obeying commands; they are accustomed to following their own desires. The driver has never been taught the language of the horses, what to feed them, or how to groom them. Nor does he know whom to ask for instructions about where to go.

Applying this to Marta, Gandolfo and Roberta: Marta’s impulsive decision to quit her job stems from her emotional function. Her galloping horses drag her driver and carriage over a cliff from which recovery will come at great cost. Gandolfo’s inability to change course is rooted in his motor function. His carriage is stuck in a familiar path and is resistant to change. Roberta’s obsessive planning is driven by her thinking function. Her driver micromanages her horses and carriage, attempting to do what they could do much more efficiently for themselves. Each suffers from an imbalance between horse, carriage, and driver that impedes their functioning and causes them to suffer.

Micro-Cosmos Human as Three-Brained Being

Micro-Cosmos Human as Three-Brained Being

Micro-Cosmos Human as Three-Brained Being

The Master of the Carriage

Carriage, driver, and horses will fall out of balance as long as the fourth element of our metaphor is missing: the master. It is the very absence of an overseeing and governing element that makes this imbalance inevitable. Nothing is present to witness and correct our deviations. Marta cannot see her impulsiveness, Gandolfo cannot see his fixation, Roberta cannot see her obsession (although their imbalance is probably obvious to everyone around them). Functioning unsupervised, carriage, horses, and driver do whatever they want, bringing upon their owners the corresponding consequences.

This is our condition before we begin any organized work, and indeed, this consequent suffering is what typically draws us to work on ourselves. We possess a carriage with full capacity for directed movement but no real direction. We possess a driver who knows how to navigate but doesn’t know where to go. And we have horses whose immense energy is consumed solely in satisfying their desires. Each component works, yet the whole is dysfunctional. To introduce harmony to our different parts, we must learn to observe them in action.

[GURDJIEFF] Self-observation is very difficult. The more you try, the more clearly you will see this. At present you should practice it not for results but to understand that you cannot observe yourselves. In the past you imagined that you saw and knew yourselves… Objectively you cannot see yourselves for a single minute, because it is a different function, the function of the master.iii

Siddhartha Encounters an Old Man

Siddhartha Encounters a Dead Man

The Metaphor of the Carriage in Buddhism

The story of Prince Siddhartha illustrates the development of a master. Before his enlightenment, Siddhartha exemplifies our ordinary state: possessing a carriage, horses, and driver, but lacking the master’s oversight. His father, King Ayodhya, determined to prevent his son from becoming a spiritual seeker, creates an artificial environment intended to keep these parts permanently imbalanced. The young prince is enclosed from birth in a palace of luxury, where his carriage (body) is pampered, his horses (emotions) are constantly gratified, and his driver (mind) is conditioned with curated knowledge.

The first stirring of the master begins with an inexplicable curiosity, a doubt in the completeness of our familiar world. For Siddhartha, this manifests as a yearning to venture beyond the palace walls. His father, understanding the danger this poses to his plans, devises a controlled exposure: he arranges a royal procession through carefully manicured streets, cleared of anything that might provoke his son’s questioning.

Siddhartha embarks on his journey of discovery mounted on a golden chariot, drawn by four horses and steered by his charioteer. Here the carriage, horse and driver metaphor comes into play. Seated atop the carriage, and being guided by his driver, Siddhartha plays the role of an infant master; he is about to witness the truth about the world outside his palace.

Despite the king’s precautions, reality breaks through. An old man crosses Siddhartha’s path, and for the first time, the prince witnesses the effects of aging. His charioteer (the mind) becomes the interpreter of this shocking sight, explaining how age affects all beings. This exchange between Siddhartha and his charioteer illustrates the proper relationship between master and driver: the master observes while the driver provides context and understanding.

The moment Gandolfo sees his fixation in his toxic relationship—the moment he realizes that his inability to change course is the source of his suffering and not his partner—marks an epiphany of the same magnitude as Siddhartha’s witnessing old age. He cannot go back to his former ignorance. The same with Marta’s impulsiveness or Roberta’s obsession with planning every aspect of her life. The moment we see that our psychological imbalance is the source of our suffering is a moment of true freedom. We now know that the keys lie in our own hands. And although much work must follow to bring this budding realization into fruition, we have taken the first step towards establishing the fourth element of our horse, carriage, and driver: the Master.

[GURDJIEFF] There are a great many chemical processes that can take place only in the absence of light. Exactly in the same way many psychic processes can take place only in the dark. Even a feeble light of consciousness is enough to change completely the character of a process, while it makes many of them altogether impossible. iv

[To be continued]

Siddhartha Encounters an Old Man

Siddhartha Encounters a Sick Man

Siddhartha Encounters a Sick Man

Sources

- Katha Upanishad, 1.3.3-4

- Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson by George Ivanovich Gurdjieff

- Views from the Real World by George Ivanovich Gurdjieff

- In Search of the Miraculous by Peter Deminaovich Ouspensky

Continue Reading: