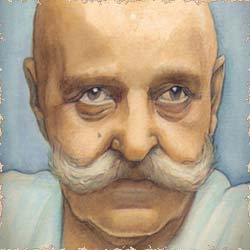

Gurdjieff in Kashgar (Early 1900s)

Part IV of Seeker of Truth recounts a moment of impasse in Gurdjieff’s development. After a decade of searching for truth, he has come to realize the value of self-remembering—of retaining a sense of “I am here” always and everywhere—but he cannot do it. He realizes that unless he finds something to constantly remind him, the flow of mental associations will always cause him to forget. He realizes that such an alarm clock can only come from inside, through sacrificing a chief feature of his psychology. “The question arises,” he concludes, “What is there contained in my general presence which, if I should remove it from myself, would always be reminding me of itself?” i

Our psychology lends itself to such a sacrifice. While we are a multiplicity of brains with a multiplicity of impulses, all converge at a single point. “Our habitual emotions, the way we think, what we invent,” explained Peter Ouspensky “all turn around one axle and that axle is chief feature.” ii Assign an alarm to this axle, and you wind a clock that reliably reminds you at every turn.

Gurdjieff in Kashgar (Early 1900s)

Gurdjieff in Tibet

Gurdjieff’s realization of the need for a permanent reminding factor happens during his two-year sojourn in Tibet, in 1902-1904. Here, in a clash between two tribes, he is injured by a stray bullet and spends a few months convalescing. Under severe pain, he examines his efforts at applying what he had learned from his search for truth so far, and is deeply disappointed.

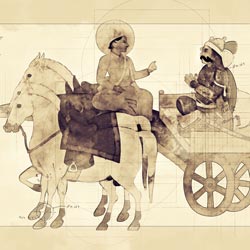

Here in Tibet, Gurdjieff would likely have become familiar with a teaching that portrays human psychology as a wheel with a chief feature at its axle: the Tibetan Wheel of Life. This presentation came from the founder of Buddhism himself, Gautama Buddha. When he gave his first sermon in Varanasi in Northern India, he reputedly drew a wheel on the sand that illustrated the root of human ignorance and suffering: the cycle of samsara. This lesson came to be known as the Turning of the Wheel of the Law, and the wheel became the symbol of Buddha’s teaching.

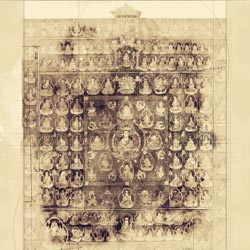

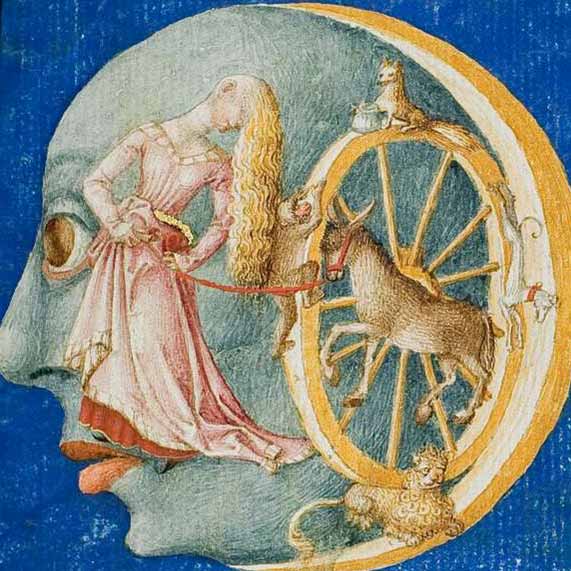

The Wheel of Life

A nineteenth-century Tibetan tankha portrays the Wheel of Dharma two and a half millennia after Buddha drew it on sand. Like a snowball, the wheel has accumulated layer upon layer of elaboration. The most striking impression of this composition is Yama, the fiery-red lord of death who hugs the wheel with his legs, arms and teeth. Whatever human life is, it is framed and dwarfed by death.

Buddha’s psychological wheel is comprised of four concentric circles. The first is a hub that bears three animals on a red background. The second shows eight monks ascending and descending. The third is divided into six densely populated worlds. And the fourth creates the rim with twelve oval-like scenes. In examining chief feature, our primary concern in this wheel is its hub.

Wheel of Dharma

Wheel of Dharma

Greed, Anger, and Ignorance

“People beset by craving circle round and round, like a hare ensnared in a net, therefore, let the monk who desires freedom from passion abandon craving,” says the Dhammapada. And indeed, we find craving at the center of the Tibetan Wheel of Life. At its hub are featured a rooster, a pig, and a snake signifying desire, ignorance, and hate respectively—forever chasing each other. These are the three traits that drive the wheel of unconscious life. He who wishes to stop ‘circling round and round’ must challenge them. This vicious cycle directly reflects its equivalent in human psychology. One’s chief feature is such that it can never be appeased. It cycles round and round endlessly, powering one’s entire psychology.

Human psychology is layered—just like the Tibetan Wheel. We must first peel the outer layers before we can reach the axle. It takes extensive observation of oneself and others to understand the principle of chief feature. Ultimately, it is considered a weakness, not because it is necessarily in itself a bad trait. Indeed, chief feature can often be seemingly noble: a rigorous self-discipline, a deep desire for moral justice, or an inclination to consider the needs of others. What makes it our chief weakness is our relation to it. It is the last attribute of our illusory identity we will be willing to give up. We pride ourselves in it, fight to keep it alive, and take every opportunity to manifest it.

“Thinking and thinking,” continued Gurdjieff while examining his inner work, “I came to the conclusion that if I should intentionally stop utilizing the exceptional power in my possession… of telepathy and hypnotism… then undoubtedly always and in everything its absence would be felt.”i

Categorizing Chief Features

[GURDJIEFF] “A man cannot find his own chief feature, his chief fault, by himself. This is practically a law. The teacher has to point out this feature to him and show him how to fight against it. No one else but the teacher can do this.” iii

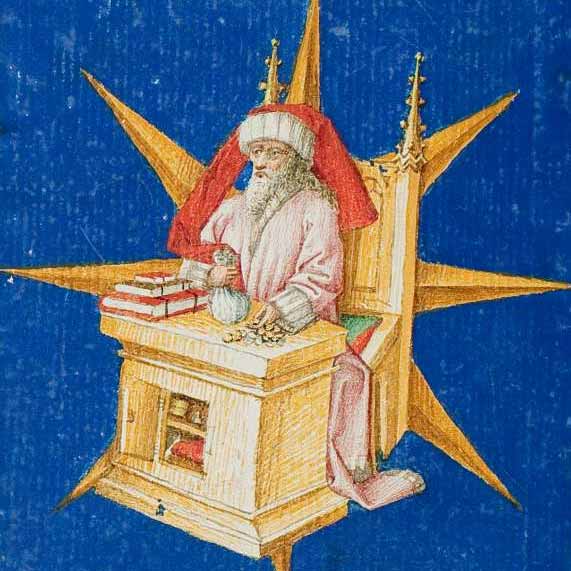

Some teachings, like the Tibetan Wheel of Life, convey the general mechanicality of human psychology. Others aim to clarify specific aspects of this mechanicality. One such teaching from the Middle Ages focuses on the hub of the wheel by categorizing the chief features that power it. This teaching drew inspiration from older schools of philosophy that correlated human behavior with planetary influences, or in other words, that mapped human psychology astrologically.

Lunatic

Mercurial

Martial

Solar

Planetary Types

The most dominant planetary influences on the human psyche were taken to be the seven heavenly luminaries most visible to the naked eye: Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Each was associated with a specific psychological character or type, and each type with a corresponding chief feature. Although no longer popular, this teaching was influential during its time and brought into literary circulation terms such as ‘lunatic,’ ‘mercurial,’ ‘venereal,’ ‘martial,’ ‘jovial,’ and ‘saturnine’—terms found in mainstream works such as Cervantes’ writings and Shakespeare’s plays.

The framework of the planetary types helps us see our chief feature by outlining a pool of features we are likely to have. Once we grasp the theory, we can, through time and inner work, match that theory with practical observation. While we have difficulty seeing the hub that powers our psychology, it is obvious to everyone else around us. Our friends and family know if we are obsessed with ourselves, although they may not know to call this Vanity feature. They know if we consistently lose sight of the whole by getting caught up in details, although they may not know to call this Lunatic. They know if we typically disappear in a crowd, although they many not know to call this the Non-Existence of the Venereal type. They know if we are control freaks, although they may not know to call this Saturnine Dominance. “It is sometimes useful to collect opinions of friends about oneself,” said Peter Ouspensky, “for this often helps in discovering one’s features….”

[GURDJIEFF] The study of the chief fault and the struggle against it constitute, as it were, each man’s individual path, but the aim must be the same for all. This aim is the realization of one’s nothingness. Only when a man has truly and sincerely arrived at the conviction of his own helplessness and nothingness and only when he feels it constantly, will he be ready for the next and much more difficult stages of the work.” iii

Venereal

Saturnine

Jovial

Obstacles in Detecting Chief Feature

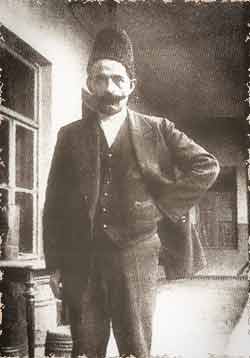

Peter Ouspensky

George Gurdjieff

[PETER OUSPENSKY] “Whenever anyone disagreed with the definition of his chief feature given by Gurdjieff, he always said that the fact that the person disagreed with him showed that he was right.” iii

The first layer of resistance is our reluctance to be categorized. We each feel special in our own way, and the prospect that our deepest traits stem from a finite number of features negates this illusion. If our characters differ only in the blend of features that power them, and in the somewhat accidental life experiences that etch themselves onto our memory, then nothing about us is unique. Our ability to see chief feature as the hub of our psychology will depend on our ability to acknowledge that we have no individuality, that we are borrowed beings, created seemingly different by force of circumstances.

[THOMAS DE HARTMANN] “From the first days Mr Gurdjieff had spoken with us about this chief weakness. To see it and to realize it is very painful, sometimes unbearable… A man must find in himself the strength not to run away from this pain, but boldly to turn the other cheek—that is, to listen and accept further truth about himself.” iv

Peter Ouspensky

George Gurdjieff

Coming to terms with our lack of individuality, we overcome the first obstacle and bump into a second one: our inability to observe ourselves. Chief feature is stimulated in the moment and triggers attitudes that manifest in the moment. We can see it best when it is most active, but when it is most active we are most blindly asleep. A casual comment from a bystander; the realization that we will be late for an important meeting; the frustration of seeing our plans crumble—these all trigger reactions within us directly related to our chief features. To observe them, we must develop an observer separate from them. We must learn to see in real time.

Our growing ability to observe ourselves thrusts us before a third obstacle: underestimating the depth of chief feature. Disliking what we see, we are tempted to remove what we see. We hurry to clear the weeds without regard to their root. But since chief feature cannot be removed without damaging our psychology—as the hub of a wheel cannot be removed without damaging the wheel—so inevitably chief feature undertakes work on chief feature. A person with vanity feature interprets this diagnosis to mean they must eliminate vanity and become perfect; one with dominance plans how to dominate his feature; one with power how to overpower it. Thus, the serpent consumes its own tail and we continue revolving mechanically around the same psychological hub.

This hopeless revolution, by which we consistently end up at the same starting point, eventually reveals to us our chief feature, as well as the humility necessary for working with it consciously.

[BENNETT] “At last, I began to understand something. Gurdjieff was making greater and greater demands upon me. Some were absurd and even impossible. It dawned upon me finally that I could and must learn to say “No.” It was like a blinding light. The inability to say “No” was my greatest weakness. He had stretched this weakness to breaking point, without explaining why, or what he was doing. Of course he could not explain, or the task itself would have vanished.” v

Thomas de Hartmann

John Bennett

Thomas de Hartmann

John Bennett

Chief Feature as Achilles Heel

Injured Achilles | Peter Paul Rubens

One of the most well-known portrayals of chief weakness is featured in the Greek myth of Achilles.

Achilles’ mother, the goddess Thetis, immerses him in his infancy in the river Styx, holding to him by his ankle. The magical waters render him invulnerable wherever they touch his body; everywhere but the area covered by her dipping hand. As a result, Achilles becomes mostly invulnerable, while only his heel remains exposed to human attack.

The location of this vulnerability is meaningful. Physically speaking, we perceive danger through our five senses. Four of these are located on our heads facing forward: our eyes, nose, mouth, and ears. The heel is the part of our body farthest away from our faces, from our senses, and consequently, from our supervision. Anything that approaches us from our heel is bound to catch us off guard.

This physical vulnerability of Achilles corresponds to the psychological blind spot of chief feature. Blindness is a fundamental trait of chief feature. “One can hardly ever find one’s own chief feature” said Peter Ouspensky, “because one is in it, and if one is told, one usually does not believe it.” ii Blind to what determines our own conduct, we remain blind to our deepest traits unless shown by someone else. And indeed, Achilles is ultimately slain through an injury to this very spot, when an arrow pierces his heel.

Injured Achilles | Peter Paul Rubens

Achilles | Detail of Arrow

Achilles | Detail of Arrow

Hercules Fighting the Hydra

A wound to the heel is bound to be painful but not fatal. What renders the arrow that slays Achilles lethal is poison. It is dipped in the blood of the Hydra, a mythological snake-like monster with several heads. This monster, too, relates to chief feature, for it is endowed with the peculiar trait that if any of its heads are cut off, two more spring out of the fresh wound. The image of endless heads cropping out of a single body echoes the principle of chief feature; a hub from which stem all the spokes of our psychology.

Hercules Fighting the Hydra

Chief Weakness and Chief Strength

We began our survey of chief feature with Gurdjieff’s realization that he had to formulate an effort around the hub of his psychology. He asked himself, “What is there in my general presence which, if I should remove it from myself, would always be reminding me of itself?”i

“Thinking and thinking,” continued Gurdjieff, “I came to the conclusion that if I should intentionally stop utilizing my exceptional power… of telepathy and hypnotism… then undoubtedly always and in everything its absence would be felt.” i These powers, obviously advantageous in everyday life, had proven disadvantageous for Gurdjieff’s inner work. Something he had always considered to be a strength had now proven to be a weakness. “Thanks mainly to this my inherency,” continued Gurdjieff, “I [had been] spoiled and depraved to the core, so that most likely this would remain for all my life.” i

The conundrum that a trait of our psychology would simultaneously be a strength and weakness is the hallmark of chief feature, and forms the basis of Esoteric Christianity.

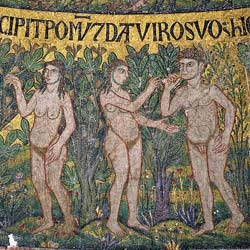

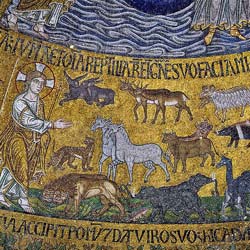

God Creates Vegetation | San Marco

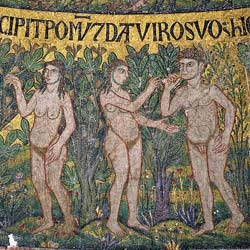

God Commands Adam and Eve | San Marco

Chief Feature in Esoteric Christianity

In the Book of Genesis, God creates a Paradise and populates it with plant and animal life. He entrusts its keeping to Adam and Eve. They may enjoy Paradise on the condition that they avoid the fruit of the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. The serpent tempts them to break this command, and consequently affects their fall.

Apart from losing Paradise, all parties involved in this crime receive personal punishment: Adam is cursed to labor for bread for the rest of his life; Eve to suffer in bearing children; the serpent to crawl on his belly. To the serpent, God says, “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; it shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.

God Commands Adam and Eve | San Marco

Temptation | San Marco

God Creates Animals | San Marco

Temptation | San Marco

Adam and Eve | Kremlin

The mention of heel—the very blind spot so central in the Achilles myth—might be dismissed as coincidental, except that Orthodox Christian depictions of this scene emphasize it beyond doubt. In their presentations of the Last Judgment, Adam and Eve are shown crouching before Christ the judge, begging forgiveness for their sin of biting on the forbidden fruit. A large serpent is poised to pull Adam all the way down to the hell, if Adam doesn’t watch his heel, because that’s where the serpent’s fangs are headed.

The Biblical story of the fall of mankind sets the stage for its redemption. Through conscious labor (the curse of Adam) and voluntary suffering (the curse of Eve), Paradise can be regained. Taken as a whole, the story of Jesus—who labors and suffers and eventually pays the ultimate price of self-sacrifice—redeems Paradise, turning the weakness of chief feature into a strength.

In this way, Esoteric Christianity lays down the theory of renouncing chief feature, yet it remains up to each individual to translate this theory into practice. As chief feature differs from one person to another, so must its sacrifice. First, the blindness must be removed; one must uncover the hub of one’s psychology through extensive self-observation. Then one must repeatedly see and suffer its consequences. And only then, will one have the knowledge and will-power to renounce it.

[GURDJIEFF] “As soon as I realized the sense of this idea, I was as if reincarnated; I got up and began to run around… without knowing what I was doing, like a young calf. It all ended thus, that I decided to take an oath… never again to make use of this property of mine.” vi

Adam and Eve | Kremlin

Detail of Serpent Biting Adam’s Heel

Detail of Serpent Biting Adam’s Heel

Frequently Asked Questions

What is chief feature in Gurdjieff's teaching?

Why is understanding the chief feature considered important in the Gurdjieff Work?

Your chief feature blocks consciousness.

– Chief feature is central to the False Personality we acquire from imitation, social conditioning or other forms of adaptation to the external world

– Observing and understanding Chief Feature is therefore crucial to being able to see our mechanicality.

– When we interact with the world from our mechanical False Personality, we fail to really take in new impressions

– By deflecting new impressions, False Personality prevents our consciousness from taking in experiences and growing from them

– By working against our Chief Feature, we weaken our False Personality and give our innate Essence the freedom to have new experiences and to grow

It’s the root of your mechanical behaviors.

– There is a certain efficiency and convenience in having ready-made reactions and responses to Life

– However, the overgrowth of this capability means that we lose our sense of wonder, fail to take things in new way or to grow from our experiences

– We sense things superficially, in predefined categories and have habitual reactions to them

– Rather than seeing this as a potentially useful tool, we think that our acquired and habitual ways of relating the world are what we actually are at our core

– We reduce ourselves to our and dislikes, our opinions or habits

Without identifying it and struggling with it, other efforts can become superficial or even feed the false self.

– Over time, these notions and reactions compound themselves, increasing our efficiency but reducing our capacity for self-knowledge

– The inevitable difficulties and surprises of life are quickly assimilated by False Personality to reduce the friction and impetus for reflection that they would otherwise cause

– We fit our perceptions automatically into pre-built categories, or take things in a way that fit with our existing beliefs about ourselves and the world

– For example, fear becomes a habitual reaction to things that would require us to make efforts or take risks that might require too much energy or challenge our belief system

“The struggle against one’s chief fault is the most important part of the work… It must proceed in deeds, not in words.” — Gurdjieff

Facing it is uncomfortable — but necessary. It’s like locating the main knot in your psyche if you ever hope to untangle the rest.

How do I identify my chief feature?

– It’s recurring — a pattern you’ve repeated for years. It’s a trusted and ingrained response which our psychology follows, like a needle in the grooves of a record

– It often shows in crisis, conflict, or embarrassment as these are the ‘bumps in the road’ that the False Personality wants to smooth over

– You’ll resist seeing it — and that resistance is often the clue. Seeing our False Personality defeats the purpose for which it exists, to keep us going comfortably along in a state of sleep

– It usually feels like “just how I am” — which makes it invisible. Our familiarity with this Feature over years of repetition causes us to believe that it is us

– It can show up as a default emotional reaction (e.g., sulking, anger, fear) Gurdjieff would deliberately provoke students to expose this feature.

“Whenever anyone disagreed with the definition of his chief feature given by Gurdjieff, he always said that the fact that the person disagreed with him showed that he was right.” — Ouspensky

Can you give examples of common chief features?

– Vanity – needing admiration, fearing being seen as ordinary

– Self-pity – feeling chronically misunderstood or mistreated

– Fear – always anticipating danger, hesitating to act

– Laziness – emotional inertia masked by busyness or distraction

– Greed – not just for things, but attention or security

– Sentimentality – clinging to emotion or romanticizing the past

– Need for control – over people, outcomes, or even feelings

– Pride – refusal to admit mistakes or weakness

– Stubbornness – habitual resistance, even when it harms progress

– Identification with suffering – using pain or hardship to define oneself

Each of these can wear many disguises — including “good intentions.”

How can I overcome my chief feature?

Here’s how:

Self-observation

– Notice when it appears. Track it. Especially:

– When you’re triggered

– When you’re defending yourself

– When you’re avoiding responsibility

Self-remembering

– Be present in the moment it shows up. Feel the discomfort. Hold both the impulse and the awareness of it.

– This creates friction — the key to inner growth. Without understanding this friction causes strife, but with a teaching to guide you, it can be harnessed to increase consciousness

Task work – Often, teachers give students tasks that directly confront their feature:

– Someone who avoids conflict may be asked to speak in public.

– A proud person might be told to sweep floors or serve others.

– A sentimental person may be told to detach from stories and simply observe.

Accept help

– Feedback from others in a Gurdjieff group is crucial. It’s hard to see what we’re too identified with.

– The rapport and mutual respect that groups foster provide an ideal environment for receiving ‘photographs’ about our Features

– They are presented compassionately, in the context of an objective system of psychology and given with the knowledge that the ‘photographer’ also has their own Features and False Personality that they are working to overcome

Persist over time – This is not a quick fix — it’s a life’s work. But each time you face your chief feature and resist being ruled by it, something strengthens inside.

“The only chance of salvation is for a group of the more sensible servants to meet together and elect a temporary steward…” — Gurdjieff

That steward is the part of you that starts to direct your life consciously, instead of being hijacked by your feature.

– The steward sits above our False Personality and therefore has freedom from its habitual reactions

– This freedom is what allows us to have genuine will and choice

– This also allows the steward to have a greater connection to our inherent likes and dislikes, talents and ways of being rather than the ones we learned or acquired to protect against Life

– It is more in touch with our Nature and because it is not habitual, it has more opportunity to learn and grow

Sources

- Life is Real Only Then, When ‘I Am’ by George Ivanovich Gurdjieff

- The Fourth Way by Peter Ouspenaky

- In Search of the Miraculous by Peter Deminaovich Ouspensky

- Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff by Thomas and Olga de Hartmann

- Witness by John Godolphin Bennett

Continue Reading: